Andrew is a music connoisseur and right now he is in the mood for something more serious and solemn. He pushes a CD of French-American cellist Yo-Yo Ma into the CD player in his 4X4: Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites fill the car. Rather sombre, it is the perfect music to catch the mood of a landscape that explorer John Edward Eyre called “one vast dreary waste”.

We are below sea level, on the shores of Lake Eyre South. A blinding, shimmering expanse of salt disappears into infinity. The surrounding land is flat, covered in stunted vegetation, the sky huge. There is a sense of exposure, and no sign of life. But let it rain up in far away Queensland, let a cyclone dump its load into the catchments of the Diamantina River and Cooper Creek, and the scenario will change. Murky floodwaters will then slowly travel over hundreds of kilometers and fill the lake. Then life will explode.

Not far from the shores of Lake Eyre South, surrounded by barren sand and gravel plains, is life. Strange mounds, some covered in grass and reeds, interrupt the flatness like mini volcanoes, their craters not filled with boiling lava but water – mound springs. Little finches twitter hyperactively around, and dragonflies zip through the air.

The area around the springs is an ancient waste dump: flakes, core stones, occasionally a beautifully crafted spear head, grinding stones. A long time ago, craftsmen of the Arabana people skillfully created stone tools here while their families camped around the springs and kids played in the vicinity of life-giving water.

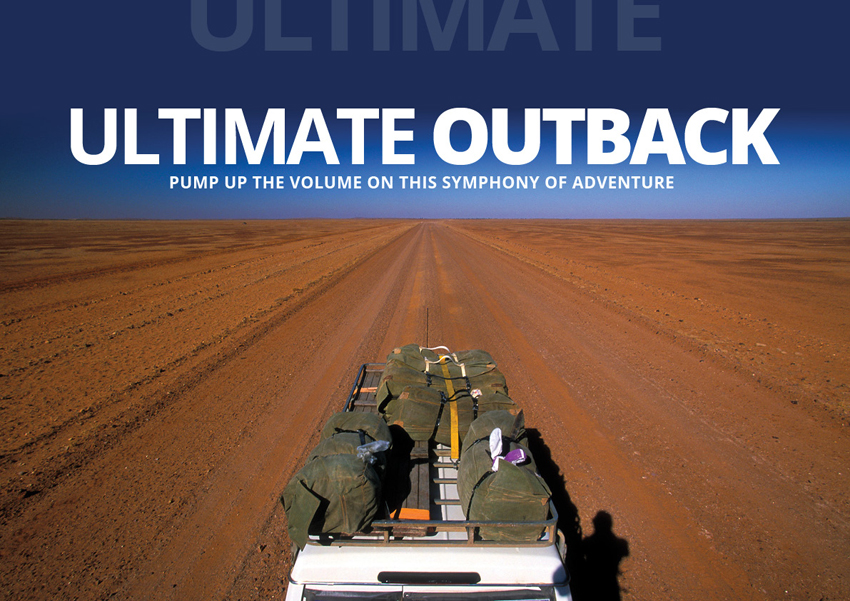

My friend Andrew, a wannabe-DJ with an eclectic taste in music, is a former chef and irrevocably taken by the sparse beauty of Australia’s arid interior. With him on this trip are his other two buddies: John, a doctor from London, and the bearded giant Simon. It is not quite clear what he actually does. We are on a journey through perhaps the most inhospitable areas of Australia: the great salt lakes of South Australia, the lifeless expanses along the Oodnadatta tracks, the waterless Simpson Desert, the desolate Martian landscape along the Birdsville Track, the desert mountains of the Flinders Ranges. It is a journey through what Andrew calls “The Ultimate Outback”, a journey through the highlights of Australia’s arid interior.

Like a dotted line on a map, mound springs follow the western rim of the artesian basin and mark an ancient trade route from the Flinders Ranges to central Australia and beyond, used by Aboriginal people over thousands of years. These springs made it possible for humans to venture into a vast and hostile country.

Explorer John McDouall Stuart took advantage of the springs on his epic crossing of the continent from south to north in 1862. Nowadays the unsealed 619km Oodnadatta Track mainly follows his route and marks part of the Overland Telegraph line which joined Australia with Java and ultimately Europe. Parallel to the Oodnadatta Track runs the original Ghan railway line between Adelaide and Alice Springs.

It is mid morning, the air still crisp, the sky a light hazy blue. Just off the Oodnadatta Track is the railway siding of Curdimurka. A red water tower, a restored shed, and a few kilometres of rail are reminiscent of the old days, when steam engines pulled carriages through this arid country. Once there was life here, sounds, people. Now it is only silence, but a silence that can tell so much. What was once a lifeline is now reduced to a string of ruins: Curdimurka; Beresford, which had giant water softeners to prepare water for the steam locomotives; the 578m Algebuckina Bridge over the Neales River.

Then there are the ruins of a repeater station at Strangways Springs, Peake with its photogenic ruins of the old telegraph station and the copper mine on the hill behind. The common denominator along the track is water, and although many of the springs have dried up, in Wamba Kadarbu Conservation Park two active mound springs, Blanche Cup and The Bubbler, can be visited. The water bubbling out of the ground fell as rain two million years ago and 2000km away.

The old narrow-gauge Ghan railway arrived in Oodnadatta in 1891 and it seems not much has changed since the years between 1891 and 1929, when the town was an important railhead. Although the famous Pink Roadhouse now dominates the southern end of town and the days where all freight was loaded onto camel backs for the journey on to Alice Springs are over, the outback town has preserved its pioneer character.

About 100km after Oodnadatta a track leads east through Hamilton Station and on to Dalhousie Springs. Black storm clouds are gathering, and the sun dips below and bathes the landscape in an unearthly light. It’s like a road movie. Andrew chooses blues and Eric Clapton sings “I’m gonna shoot my pistol, gonna shoot my Gatlin’ gun. You made me love you, now your man has come”. Our feet tap, the scenery in panoramic format and technicolor passes by.

At Dalhousie Springs, the largest outlet of the artesian basin, we immerse ourselves in 38-degree warm soft water. It is an absolute luxury in this arid country. From now on, water becomes very scarce. Dalhousie Springs, a vast oasis of 80 square kilometers and part of Witjira National Park, lies at the edge of the Simpson Desert, where no permanent surface water, apart from the artificial wetland at the uncapped Purni Bore, will be encountered.

The Simpson Desert is one of the world’s great sand-ridge deserts with an area six times the size of Belgium. A low cloud cover and a cold wind create a bleak atmosphere on that first day. Camp is in a clay pan between two sand dunes. Gnarly trees, the famous gidgee tree or stink wattle, grow in the vicinity. They supply “the champagne of firewood”, according to Andrew. On the edge of the pan, baked in clay, I find stone tools. Aborigines lived a nomadic life for at least 5000 years in this desert, following a string of nine wells that they maintained. That evening Mario Lanza’s divine voice at full volume echoes across the desert expanse. Arreviderci Roma! Andrew cooks Italian. Only the wine is Australian.

The nature of this vast desert remained unknown to Europeans until 1929, when geologist Cecil Madigan flew over it. From his plane he saw a sea of parallel dunes like sand flats at low tide. The first recorded crossing by a European took place in 1936 when local bushman Ted Colson rode across the innumerable sand dunes to Birdsville and back. His incredible achievement becomes clear over the next few days, when our vehicles get a true workout, battling sandy tracks, climbing mighty dunes, crossing soft and wet clay pans due to recent rain.

The Simpson Desert’s beauty is not obvious. Getting through is a challenge and many hours are spent in the vehicle every day. Many a dune needs several attempts. It all depends on the driving technique. And the weather. “We are lucky that it is relatively cool,” says Andrew. “If it is really hot, the sand becomes liquid.” Come late afternoon, when camp is established, we venture up to the crest of the nearest sand dune. The sand takes on a deep red in the low sun. A multitude of animal tracks are evidence that the desert is full of life. Ripple marks and wind-created patterns grace the sand. The hidden beauty of the Simpson Desert becomes apparent and has a deep impact on us.

The last sand dune on the way to Birdsville is a celebrity. It even has a name: Big Red. The last and highest obstacle, it marks the end of the Simpson. From the ridge of the giant sand dune the view goes out into the flat, heat-shimmering wasteland. Not far from here lies Birdsville. It offers all the mod cons we are used to, including a famous pub. The sense of adventure, the feeling of insignificance out there between the dunes, is left behind.

Further south along the Birdsville Track we could be on Mars. The famous stock route leads through a flat red expanse of polished gravel: gibber plains. Mirages lure in the distance. The track flanks the Simpson Desert, runs through Sturt Stony Desert and between the Tiara and Strzelecki Deserts. Through this forbidden landscape stockmen used to drive cattle south to Maree, where they loaded them onto trains bound for the slaughterhouse. In 1972 road trains took over and the era of epic cattle drives through the desert ended.

In Maree the circle closes. The Oodnadatta Track and the Birdsville Track meet here. At the railway station, two narrow-gauge diesel-electric locomotives used on the old Ghan are restored and on display. Another one, defaced by grafitti, sits rusting in the sun where the track used to head north, out into the desert. The rails are gone, pulled up and sent to the Queensland cane fields in 1981.

Further south of Maree the flatness of the country makes room for the peaks, ridges and hills of the Flinders Ranges. Ry Cooder’s haunting slow guitar riffs from the movie Paris, Texas pour out of the speakers on the way through the barren northern Flinders Ranges to Chambers Gorge and the mighty Mount Chambers. It seems just right: the simplicity of his music, its melancholy grabs the soul – just like the outback.