Advertisement

Advertisement

It’s not uncommon knowledge that our sunburnt country is home to some of the deadliest animals in the world. Whether they crawl the earth or swim in the sea, we have a selection that you’ll want to cross your fingers you don’t come across.

We decided to list the 5 deadliest Aussie animals that you may encounter along with some facts about them. Read to the end to learn what you’ll need in your first aid kit, plus a pressure immobilisation technique.

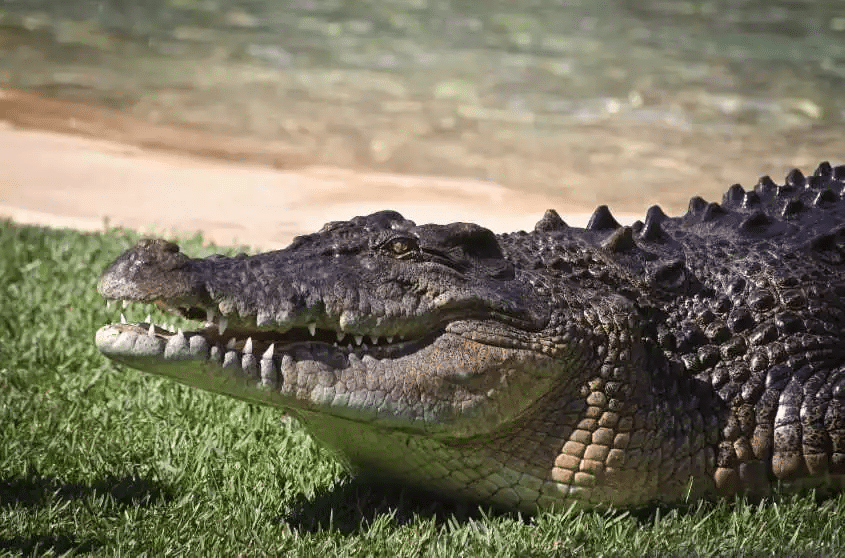

The Australian saltwater crocodile is just about the perfect killing machine when it comes to animals. So much so that many people up in the far north of Australia would rather shoot them on sight than allow them to move into their local waterways. Just for the record, this is illegal without a licence. There are numerous anecdotal reports that dams used to be safe to swim in 10 years ago in the Kimberley area. However, they are now home to very territorial male crocs and you wouldn’t want to dip a toe in.

And that’s where the danger comes in. These guys stake out their areas and don’t like walking kebabs (humans) coming in and trespassing on their property.

While you don’t need to be paranoid about croc attacks, when you’re north of Hervey Bay it pays to be aware of the dangers. These guys are the largest reptiles in the world in terms of mass, with the males getting up around 6-7 metres in length. Although even 5 metre crocs are fairly rare (and still frickin’ huge).

On average, salties kill one or two people a year and despite the name, are commonly found in freshwater estuaries, creeks, rivers, dams and billabongs, as well as along the coast. So if you’re travelling up north near water, ask the locals about where it’s safe to swim and fish, and where to avoid. Even then, take plenty of care around bodies of water. This includes staying away from the water’s edge. Don’t be predictable in your routine around the water (crocs hunt by learning your movements) and don’t wade in shallow water. Make sure you use a bit of common sense and leave the bacon tracksuit at home eh guys? Also, take special care around September to April, which is breeding season. Crocs can be especially aggressive during this time.

We’ve all heard the terrifying facts on inland taipans, or fierce snakes, and how one drop of venom can kill 100 people. They can strike incredibly quickly and if you see one coming towards you, move… like, to another state.

Despite all the hype surrounding the most venomous snakes in the world, they don’t pose a massive risk to us homo-sapiens for a couple of good reasons. The first is their habitat. They like to reside in the sparsely populated arid regions around the QLD, SA and NT borders. So basically, if you’re planning a trip through the Simmo or to Poeppels Corner, keep an eye out. But for 99.9% of the population they’re not worth worrying about.

The second reason is that unlike their cousins, the coastal taipans, the inland taipans are actually quite shy and are more likely to retreat and hide than attack. You’d have to provoke or mishandle one to get bit (which begs the question: Why the hell would you mishandle a bloody taipan? It’s practically begging for a Darwin award). And even if you do happen to get a pair of puncture wounds, the chances are good you’ll live to tell the tale. The first step after a bite is to immobilise the limb before covering it completely with a pressure immobilisation bandage (see separate panel on how to do this) and splinting the affected limb to prevent undue movement. Don’t try to clean the wound or suck out the venom. Just hightail it to the nearest medical facility and get some anti-venom into you as soon as you can

Funnel-webs are found along the east coast of Australia. While they’re most commonly observed in NSW, they can also be found in QLD, SA and VIC and are not to be taken lightly. Commonly regarded as among the most venomous spiders in the world, these buggers are also quite aggressive. So if you see one in your home, you won’t be judged harshly if you decide to burn the house down!

OK, that may be taking things a little far; but still, copping a bite is no joke. Interestingly, since the introduction of widely accessible anti-venom in the 1980s there have been no fatalities from funnel-web bites. However I’ve seen first-hand how much these things can cause your life to suck should one get its fangs (which are powerful enough to go through soft shoes) into you.

A mate of mine accidentally trod on one when we were camping up near a tidal estuary on the north coast of NSW and it nipped him on the side of his foot. Luckily, all of us there had our first aid certificates up to date and we applied a pressure immobilisation bandage (as a note, the funnel-web is the only spider with which you should use this technique) and got him to the hospital which was about an hour’s drive away. Three painful and uncomfortable days later and he had a hell of a story to tell. But I’m sure he would’ve rather skipped the experience if he’d had the option.

Funnel-webs live in moist, cool and sheltered habitats where they make their funnel-shaped burrows (hence the name) that they line with irregular web trip lines tracing from the entrance. If you see one, best avoid it.

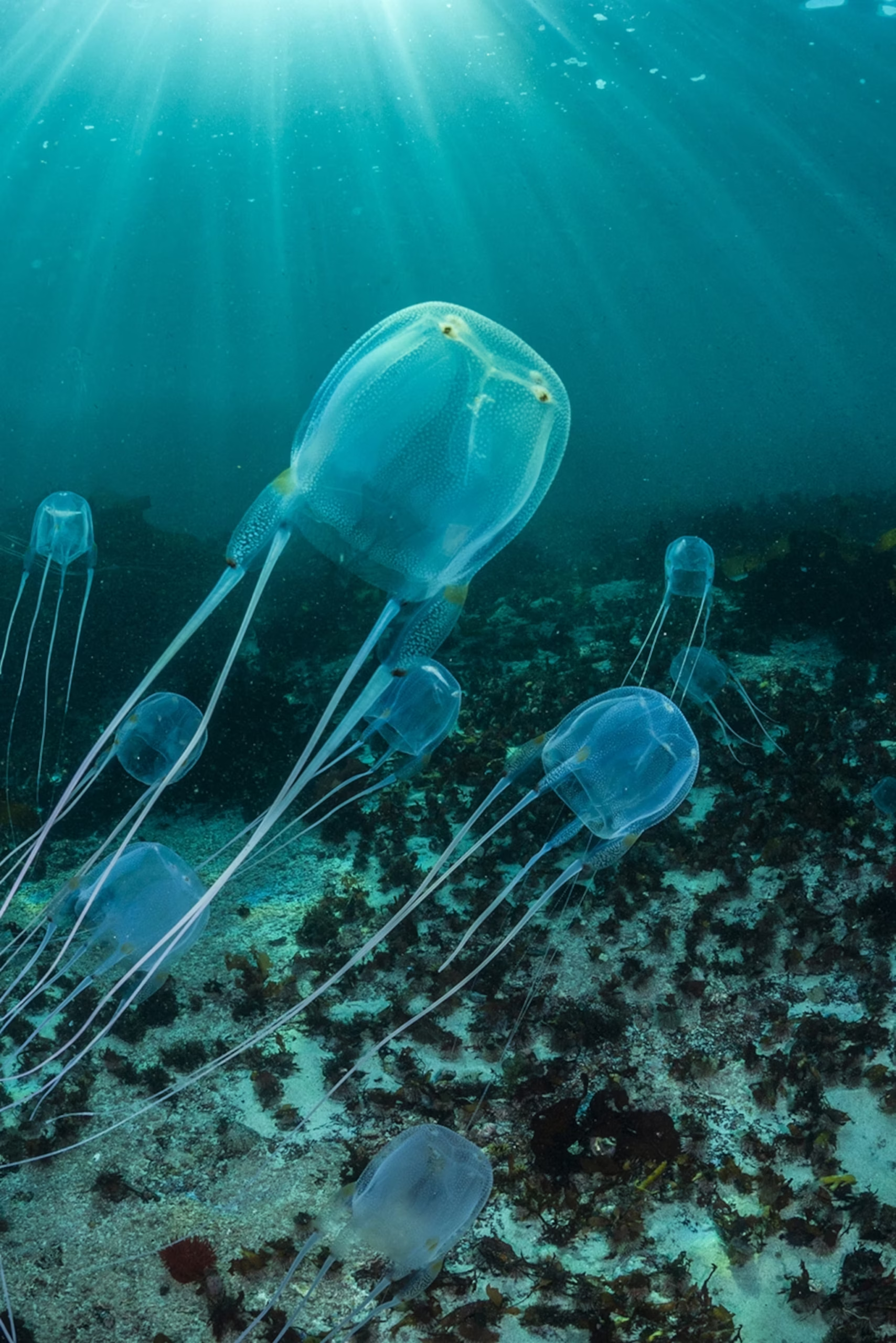

While you may be more concerned about great white, bull or tiger sharks when you jump in the ocean, spare a thought for the box jellyfish. It’s the most venomous marine animal in the world and hangs around northern Australia (especially during the wet season).

Interestingly, these straight-out-of-a-Peter-Benchley-novel terrors are not actually true jellyfish. They actively swim after their prey, as opposed to true jellyfish that aimlessly drift on the currents.

These animals have a box-shaped head (as you’d guess) and tentacles up to 3 metres long. They’re clear with a blue tinge, making them almost invisible in the water.

Fun fact one: The stings affect the heart, the nervous system and the skin. So coming into contact with one sounds like an absolute joy… They’ve been responsible for a fair few deaths over the last century and even those who survive are often left with nasty scarring of the affected area. The venom can cause cardiac arrest. So if this happens to someone nearby, you need to commence CPR as soon as you can.

Luckily it’s not always that extreme. If the victim is stung somewhere non-vital, like the ankle for example, you need to inactivate the remaining stinging cells by pouring vinegar over the tentacles and soaking them for a good 30 seconds before removing them. If you try to pull them off before this step, they can actually release more venom.

Fun fact two: Ordinary vinegar has actually saved dozens of lives at Aussie beaches over the years. Interestingly, pressure immobilisation bandages as used on snake and spider bites are no longer recommended as they can cause further venom discharge, even if vinegar’s been used. Pop a couple of antihistamines and painkillers on your way to get medical treatment and a dose of anti-venom.

Metho, ammonia, urine, bicarb soda and all the other ‘remedies’ you may have heard of unfortunately don’t work… gee, may have to go chuck a bottle of vinegar in the old first aid kit.

The second-most venomous snake in the world is the eastern brown snake. It’s a highly aggressive little bugger and is found all over the place. They don’t like overly wet places like rainforests, nor overly dry places like deserts. But they fit right in everywhere else. They have a diet of mainly rodents, so they love farms and remote properties. They also like to hang out under cover – places like wood piles, rubbish dumps, fallen trees and heavy scrub are all possible brown homes (so approach them with care).

There have been numerous deaths caused by these guys. I recall once hearing that a little girl got bitten, but neglected to tell her parents until several hours later. Tragically, despite being rushed to hospital and administered anti-venom, she didn’t make it. While this is truly awful, it highlights the importance of making sure your kids, family and any visitors to the bush (who may be a little ignorant) are well aware of the dangers.

As with other snake bites, get a pressure immobilisation bandage on there and splint the bitten limb to prevent the venom being spread via the lymphatic system; then get to a medical centre for a dose of anti-venom as quick as you can.

Ensure there’s no immediate danger from the animal and rest the bitten person. It doesn’t hurt to be reassuring and tell them they’ll be OK.

Apply a crepe bandage over the bite as soon as possible.

Apply a broad pressure immobilisation bandage over the rest of the limb. You want to wrap this as tight as possible without cutting off blood supply to the limb. Start just above the fingers or toes and move upwards on the limb as far as you can – including covering the animal bite.

Splint the bandaged limb.

Keep the person from moving as much as you can. The stiller they stay, the better.

Write down the time of the bite and when the bandage was applied.

Your article “The 5 deadliest Aussie animals you may encounter” perpetuates misinformation that has gotten people killed.

The correct name for the crocs you referred to is Estuarine Crocodile (Crocodylus porous), and you should have highlighted the fact they they live in freshwater and saltwater. They can tolerate water salinities from 0% to 35%. The continued use of the term “salty” counters the efforts being made to educate the public, Australians and visitors that these apex predators can be found in any water, and it may not be safe just because its freshwater.